sitelen pona

| Part of a series on |

| Features |

| Usage |

sitelen pona (sitelen-pona) is a logographic writing system for Toki Pona designed by Sonja Lang, the creator of the language. The system is described in the book Toki Pona: The Language of Good,[1] which also features sitelen sitelen. As a logography, each word is written with its own symbol. It is typically written from left to right, in horizontal lines from top to bottom.

sitelen pona is the most commonly used original writing system in Toki Pona, and the second-most after the Latin script.[2] Learners might find sitelen pona useful for memorizing words' meanings.

The Toki Pona logo (toki-pona) functions in sitelen pona as the language's name, toki pona, written as a combined glyph.

History[edit | edit source]

Since first appearing in Toki Pona: The Language of Good in 2014, many Tokiponists and communities have expanded sitelen pona, integrated it into general Toki Pona learning resources, and created fonts and text encoding schemes.

Glyphs[edit | edit source]

Original pu glyphs[edit | edit source]

The original edition of the book Toki Pona: The Language of Good (lipu pu) includes the following glyphs for each of its main 120 words.

Esperanto pu glyphs[edit | edit source]

Following the recommendations of the Toki Pona Dictionary, the Esperanto edition of lipu pu includes several additional glyphs that had already been established among sitelen pona users. Alternative glyphs for three nimi pu are presented as footnotes in the main section on sitelen pona, "Hieroglifoj" (Hieroglyphs), shown below in jan Pensa's handwriting.

Glyphs for nimi ku suli are presented in the appendix "Aldonaĵo: nimi ku suli pi pu ala". They are introduced as "the most common glyphs" as of 2022. It warns that the community did not yet fully agree about the glyphs for all words at the time, so the most accepted glyphs of some words could be different some time after 2022.[3]

Other glyphs[edit | edit source]

There are alternative glyphs for more of the aforementioned words than those presented in the Esperanto edition of Toki Pona: The Language of Good. Some of the words have multiple notable alternatives. Tokiponists have also created glyphs for many nimi sin.

Radicals[edit | edit source]

Many sitelen pona glyphs have shapes in common, which have been analyzed as "radicals".

Punctuation[edit | edit source]

Use of punctuation in sitelen pona is not officially defined. In general, the main use of punctuation is to mark the boundary between sentences. Most people use only a sentence boundary mark, and some will use a form of quotation marking.

Using Latin-script punctuation, as in English, can cause confusion. The question mark (?) and seme (seme) are homoglyphs, and the exclamation point (!) resembles the glyphs for a (a), kin (kin), and o (o). In fact, these words largely make these punctuation marks redundant.

Sentence boundaries[edit | edit source]

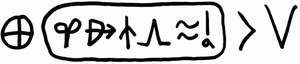

The only full sitelen pona sentence in pu, seen below, is written with no ending punctuation. This style can extend to multiple sentences. The end of a sentence can be indicated by simply adding a space, or starting the next sentence on a separate line (as used in su).

ma [kasi alasa nasin awen telo a] li sulima Kanata li suli.

Canada is huge.

Some speakers use explicit sentence-ending punctuation. The most common choices are a Latin-style period (.), the middle dot (·), and a CJK-style circular period (。). A common argument for the middle dot is that sitelen pona is typically written centered around a midline, rather than a baseline. nasin sitelen kalama also uses the middle dot inside cartouches.

Question marks[edit | edit source]

A question mark is largely unnecessary. Most standard questions are already marked with seme (seme) or the pattern X ala X. Due to the glyph for seme, using a Latin-style question mark in sitelen pona causes confusion rather than solving any, and is considered bad style.

A dedicated question mark would only be needed to clarify whether the phrase X anu X marks a statement or question. However, the majority of proficient speakers nowadays refrain from using this construction, so that all questions are explicitly marked in all modalities of speech.

Since some fonts stretch the glyph for seme to fill a fullwidth character space, there is a misconception that it looks wider or more stylized than a question mark. This can result in juxtaposing the glyph in 2 widths (so that seme? looks similar to ??). In reality, seme looks just like a normal question mark in Sonja Lang's handwriting, and many other fonts follow suit.

Colons[edit | edit source]

Similar to the Latin script, colons are frequently used in sitelen pona. A colon can be written centered between the words on either side (ijo:: ijo), or closer to the word on its left (ijo: ijo).

Some people use a right-facing ni (ni2) to avoid the need for colons. For example, below are three different ways to write the sentence mi wile e ni: sina pilin pona.

mi wile e ni:: sina pilin-pona

mi wile e ni2:: sina pilin-pona

mi wile e ni2 sina pilin-pona

nasin sitelen kalama also uses the colon inside cartouches.

Quotation marks[edit | edit source]

For marking quoted text, Latin-style quotation marks are commonly used, but corner brackets (te to) are widespread, being symmetrical around the midline. These glyphs are also used for the quotative nimi sin, te and to. It may be unclear whether to read them as words or punctuation. However, when used as punctuation, a reader may interpret them as te and to without misunderstanding the author's intent.

Word spaces[edit | edit source]

Several fonts with ASCII transcription expose a ligature using the string zz to produce a glyph-sized space character, for cases where the author wants the text to be visually indented or separated. This is best rendered using the ideographic space ( ) instead. This is especially important for people who use screen readers, which will read "zz" out loud rather than silently skipping over it.

An alternative may be typing a double space, which is even more common in fonts to get a word-sized space. However, this can cause problems on websites, because HTML condenses whitespace.

Combined glyphs[edit | edit source]

The glyph of a head word may be combined with the glyph of one modifier. These are called combined glyphs[4] or compound glyphs. There are 2 main ways of doing this:

- Stacked: The modifier glyph goes above the head glyph. kala lili becomes kala^lili.

- Scaled: The modifier glyph goes inside of the head glyph. kala lili becomes kala*lili. To allow for scalar combination, the head glyph generally must contain a single, sufficiently large, main negative space.

Extended glyphs[edit | edit source]

An extended form of the word pi (pi) is very common. The low horizontal line continues under all glyphs in the pi phrase (pi (ijo ijo)). Other characters such as prepositions are sometimes also extended in this way.

Names[edit | edit source]

Cartouches[edit | edit source]

Names are written inside a rectangle shape called a cartouche similar to acronyms, inspired by Egyptian hieroglyphs. Within a cartouche, the first phoneme of the corresponding word is read, each then strung together to form the name. While any word may be used, specific glyphs may be chosen to reflect the meaning or associations of the name. The choice of words is left up to the preference of the entity being named or, otherwise, the author of the text.

In the book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Toki Pona edition), names after the first usage are abbreviated using only the first letter of the word. For example, Dorothy's name, jan Towasi, may be spelled either as jan [tomo olin wile alasa suwi ijo] or, implied, as jan [tomo].

There is also a nonstandard but fairly common extended system for writing cartouches using syllables or morae, called nasin sitelen kalama.

Name glyphs[edit | edit source]

Some people design custom sitelen pona glyphs for their names. Like the glyphs for common words, most of these do not indicate pronunciation.

Flexible glyphs[edit | edit source]

Many sitelen pona characters are not static, and aren't supposed to be drawn the same way every time.

- akesi, pipi, soweli (akesi pipi soweli)

- The amount of legs is sometimes reduced, especially in combined glyphs to reduce glyph density. Especially akesi is commonly written with two strokes for legs (akesi) instead of three (akesi).

- jaki (jaki)

- Any scribble, usually in a single stroke dense with overlaps and (mostly) curvy lines. For example, scribbles submitted by community members to be added to linja lipamanka:

- ko (ko)

- Any blobby closed shape. For example, blobby closed shapes submitted by community members to be added to linja lipamanka:

- ku (ku)

- The symbol representing Toki Pona on the cover of lipu ku can range anywhere from a simple dot to a full Toki Pona symbol.

- mi, sina, ona (mi sina ona)

- These may be written either with a curved stroke (mi sina ona) or a straight stroke (mi sina ona).

- lete, kin (lete kin)

- The rotation of the asterisk shape is not important. In some cases it may be written with four intersecting lines instead of three, and in kin some people reduce the asterisk to an X shape.

- linja, kon, telo, pakala, mun (linja kon telo pakala mun)

- May be mirrored.

- ni (ni)

- May point to the part of the text that ni is referencing; left, up, right, down (← ↑ → ↓), or other directions, instead of the standard downwards arrow. In handwriting, it may be drawn in an extended manner, pointing toward the relevant reference. A right-facing arrow (ni>) is often used in linking ni statements. It may also be extended horizontally (ni>(--) ni<(--)).

Alternative glyphs[edit | edit source]

For various reasons, people have designed new glyphs for words that already have them. The Esperanto edition of Toki Pona: The Language of Good includes drawings of some of these.

In many sitelen pona fonts with ASCII transcription, glyphs different from the font's standard glyph can be typed by appending a number to the end of a word, such as kala1. The default variants and list of supported alternative glyphs are not consistent between fonts, so this is not a consistent method to identify glyph variants. The added numbers may also interfere with screen readers.

| Word | sitelen pona | Notes | Included in pu Epelanto? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earlier | Later | |||

| a | a | a | Diagonal punctuation stem. In some cases the stem is drawn very short, almost like a diacritic. | |

| kin | kin | kin | ||

| n | n | n | ||

| o | o | o | ||

| akesi | akesi | akesi | Only 2 strokes for legs. | |

| epiku | epiku | epiku |

Obsolete:[i] Upwards arrow, now more often used for directional ni. | |

| jaki | jaki | May be any scribble. Four different variations are included in the Esperanto translation of lipu pu. | ||

| kala | kala | kala | Two dots for eyes to match the other animal glyphs. | |

| kokosila | kokosila | kokosila |

Obsolete:[i] Star, representing the Verda Stelo. | |

| lanpan | lanpan | lanpan | Obsolete:[i] Turned pana. | |

| lanpan2 |

Obsolete:[i] Top end is a hooklike curve. | |||

| majuna | majuna | majuna |

Earlier: Turned sin. | |

| meli | meli | meli | Derived from the planetary gender symbols, possibly by analogy with tonsi (from the transgender symbol). These alternatives avoid physical stereotypes. Uncommon due to gendern't philosophy, which avoids meli and mije regardless of glyph choice. | |

| mije | mije | mije | ||

| meso | meso | meso |

Earlier: 2 vertical lines with dot between. | |

| moli | moli | moli | Low line for mouth instead of circle for head. Often used in pixelated fonts due to space constraints. | |

| namako | namako | namako |

Earlier: sin with an extra ray below. |

|

| olin | olin | olin | pilin with emitters above | |

| sewi | sewi | sewi | Earlier: Derived from Arabic اللّٰه (allāh). Sometimes used only when sewi is used to mean "God" or "holy, divine". Later: Turned anpa. Commonly called "secular sewi". Sometimes used only when sewi is used to mean "up, above". |

|

| It has been suggested elsewhere to use other religious symbols, with the possible downside of being less legible.[5] | ||||

| soko | soko | soko2 | Earlier: A mushroom with a thick stem (increasingly uncommon) Later: The stem simplified to a vertical line. Can be seen with or without a horizontal stroke for an annulus. These later variants are meant to avoid confusion with mama. |

includes only |

| soko | ||||

| uta | uta | uta | Dotless. Can create ambiguity with moku (otherwise moku; here confusable with luka uta). However, this ambiguity is not more than that which already exists with pali and kepeken (normally read as pali and kepeken respectively, but technically possible to read as luka ijo and luka ilo). | |

| wile | wile | wile | Closed to become a turned heart or pilin. While the separation of the line endings varies in handwriting, this alternative is most likely influenced by sitelen pona pona (a font and derivative script). Most differences in sitelen pona pona are rejected by sitelen pona users, but some occasionally slip in when writers want to introduce oddities. | |

Notes:

Fonts such as sitelen seli kiwen also support OpenType character variants and stylistic sets, which can be enabled:

- In Microsoft Word, in the Font dialog box → Advanced → Stylistic sets.

- In many versions of Word, the Font dialog box is directly accessed from the Ribbon → Home tab → Font group, in the lower right corner.

- In other recent versions, you can use Tell me → search for "Font Settings".

- In CSS, with the

font-feature-settingsproperty.[6]

Mirrored glyphs[edit | edit source]

sitelen pona is uncommonly written from right to left. There is no set practice for doing so. Some speakers recommend that all glyphs should be mirrored vertically, so that, for example, the glyph for soweli (soweli) faces left (soweli).

linja sike includes experimental mirrored glyphs for e, li, pi, tan (visually elipitan) at codepoints U+EC9B–U+EC9E.[7]

Text encoding[edit | edit source]

As of February 2024, there is no official Unicode support for sitelen pona. The Under-ConScript Unicode Registry (UCSUR), an unofficial registry for constructed languages, is used instead.

|

Sitelen Pona | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+F190x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F191x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F192x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F193x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F194x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F195x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F196x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F197x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| U+F198x | | | | | | | | | | |||||||

| U+F199x | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | ||

| U+F19Ax | | | | | ||||||||||||

| U+F19Bx | ||||||||||||||||

| U+F19Cx | ||||||||||||||||

| U+F19Dx | ||||||||||||||||

| U+F19Ex | ||||||||||||||||

| U+F19Fx | ||||||||||||||||

Resources[edit | edit source]

Learning resources[edit | edit source]

- o kama sona e sitelen pona, video series by musi lili

- o kama sona e sitelen pona kepeken sitelen

- sitelen pona - Toki Pona Hieroglyphics, Memrise course

- Toki Pona words sorted by usage frequency, Anki deck

Dictionaries[edit | edit source]

- lipu nimi pi toki pona taso, sitelen pona–only definitions (with pronunciation audio)

- Toki Pona Dictionary, sorted by glyph shape. Entries include sitelen Lasina. Definitions are not in Toki Pona.

Fonts[edit | edit source]

ijo Linku maintains a comprehensive list of all fonts.[8]

Fonts that support ASCII transcription ligatures can be used as a learning tool. If you type a supported word correctly, the font will turn it into a sitelen pona glyph. Building this connection between pronounceable sitelen Lasina spellings and visually meaningful sitelen pona ideographs can also help you memorize the meanings of words.

Non-linguistic use[edit | edit source]

Beyond their main use as a form of writing, sitelen pona glyphs are also used as non-linguistic symbols and fictional characters. Glyphs for animal words are often repurposed as such, to the point of becoming and further inspiring mascots of Toki Pona.

Sitelenponidos[edit | edit source]

Just as Toki Pona has inspired various other constructed languages, hence called Tokiponidos, sitelen pona has inspired various writing systems, hence called Sitelenponidos. Examples include sitelen pona pona and titi pula.

Copyright[edit | edit source]

Sonja Lang has released her original set of sitelen pona glyphs under the CC0 1.0 Universal license as of December 2021,[9] and has declared the writing system "free" as of February 2024.[10] In June 2024, a more rigorous effort began to enter the other major glyphs into the public domain,[11] to avoid any possibility of copyright objections to the Unicode proposal. Many of the glyphs in question still consist of simple geometry, universal symbols that are already in Unicode, and alterations of the glyphs that have been released into the public domain.

See also[edit | edit source]

Notes[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Lang, Sonja. (25 May 2014). Toki Pona: The Language of Good. Tawhid. ISBN 978-0978292300. OCLC 921253340. pp. 104–111.

- ↑ jan Tamalu. "Results of the 2022 Toki Pona census". GitHub. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

The data regarding writing systems is quite similar to the last [2021] census. The only significant difference is that now 71% of people reported to at least know sitelen pona, while this figure was 61% before. This might be due to new better systems to write and interact with sitelen pona in different platforms and the ensuing new content created in sitelen pona. It is nice that so many people are learning sitelen pona. To put this number in perspective, more people report to know sitelen pona than people that report that they know 8 or more of the 17 Ku suli words.

- ↑ Lang, Sonja. (1 October 2022). Tokipono: La lingvo de bono (in Esperanto). Translated by Spencer van der Meulen. ISBN 978-94-6437-609-8. p. 149. "En 2022 ĉi tiuj estis la plej oftaj signoj en sitelen pona por la apudaj ne-puaj vortoj. La komunumo ankoraŭ ne tute konsentas pri la signoj de ĉiuj vortoj, do atentu, ke la plej akceptata signo de la vorto povus esti malsama post iom da tempo." [In 2022, these were the most common gylphs in sitelen pona for the non-pu words [listed on the page next to this]. The community doesn't yet fully agree about the glyphs for all words, so be aware that the most accepted glyph of a word could be different after some time.]. [This page on Wikisource]

- ↑ Lang, Sonja. (25 May 2014). Toki Pona: The Language of Good. Tawhid. ISBN 978-0978292300. OCLC 921253340. p. 110.

- ↑ soko weka [@vanapiton]. (12 June 2022). [Informal poll posted in the

#sona-kulupuchannel in the ma pona pi toki pona Discord server]. Discord. Retrieved 6 November 2023.Concerning the sitelen pona glyph for sewi, which of these (choose all that apply)... Option

(Multiple allowed)Votes

(n = 75)Do you like the usage of: Do you use in your nasin: Arabic sewi 73 72 Secular sewi 48 22 Other religious symbols 8 2 Other 2 3 - ↑ font-feature-settings. font-feature-settings. MDN Web Docs. Retrieved 7 November 2023.

- ↑ linja sike documentation. Google Docs. Retrieved 24 October 2023.

- ↑ fonts. Google Spreadsheets. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ↑ Lang, Sonja. (1 December 2021). Toki Pona: Die Sprache des Guten (in German). Translated by Julius Strake. ISBN 979-8-7707-5525-1. p. 2.

- ↑ Baum, L. Frank. (3 February 2024). The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Toki Pona edition). Translated by Sonja Lang. Illustrated by Evan Dahm. Tawhid Press. ISBN 978-0978292379. (Original work 1900.) p. 2.

- ↑ [jnpoJuwan]. (23 June 2024). "Authorship and rights of sitelen pona glyphs". lipu-linku/sona. GitHub.

External links[edit | edit source]

- Chapter on sitelen pona in Toki Pona: The Language of Good (lipu pi jan Ne)

- Media related to sitelen pona on Wikimedia Commons

| Development and usage | jan Sonja · Toki Pona: The Language of Good (2014) · Tokiponidos · Software (Tools · Fonts) · suno pi toki pona · Toki Pona census · Toki Pona Dictionary (2021) · UCSUR · Linku · ISO 639-3 |

|---|---|

| Conventions | Phonology (Phonotactics) · Words (Tokiponization) · Grammar (Word order) · Social conventions · Writing systems (sitelen Lasina · sitelen pona · sitelen sitelen) · luka pona (sign language) · Number systems · Calendar systems · Styles (pu · pu-rism · ku · Nonstandard) |

| Philosophy | Minimalism · Context · Circumlocution · Expression · Lexicalization · Multiple sentences · Comparisons |

| Resources | Frequently asked questions · Courses · Dictionaries · Cheat sheets · Visual aids · Communities · Websites · Media |

| pu | sitelen Lasina (Latin) · sitelen pona (sitelen-pona) · sitelen sitelen |

|---|---|

| Natlang transliterations | sitelen Kililisa (Cyrillic) · sitelen Kana (Japanese) · sitelen Anku (Hangul) · sitelen Kansi (Chinese) · sitelen Alapi (Arabic) · sitelen Iwisi (Hebrew) · sitelen Elina (Greek) |

| Other | Toki Pona Script (dingbats) · sitelen pona pi jan Mimoku · ASCII syllabary · sitelen musi · sitelen ko (cuneiform) · sitelen telo · leko pona (3D) · sitelen mun (Gallifreyan) · nasin pi sitelen jelo (emoji) |

| Features | Words · Combined glyphs · Extended glyphs · Radicals · nasin sitelen kalama (pi linja lili) |

|---|---|

| Usage | History · Literature · Fonts (Guidelines) · UCSUR · ASCII · Wakalito |

![akesi[a]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5b/Akesi_alt_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png/53px-Akesi_alt_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png)

![sewi[b]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Sewi_alt_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png/76px-Sewi_alt_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png)

![namako[c]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Namako_1_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png/60px-Namako_1_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png)

![namako[d]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/Namako_2_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png/60px-Namako_2_-_sitelen_pona_tan_lipu_pu_pi_toki_Epelanto.png)